A few weeks ago, South Africa experienced a spate of riots where a number of shops, factories and warehouses in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng were looted and destroyed, leaving over 300 people dead.

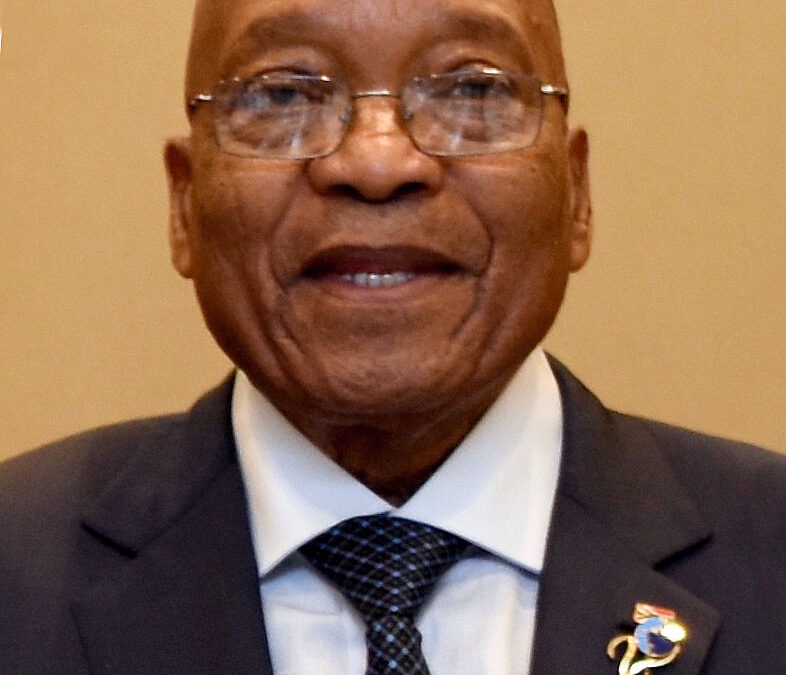

Various publications reported that this was the worst violence that South Africa has witnessed since the 1990s, which begs the question – what then caused the unrest and violence of such magnitude after 27 years of democracy? It is common cause that the unrest came after the incarceration of former President Jacob Zuma, who was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment for contempt of court for defying the Constitutional Court order to testify at the State Capture Commission of Inquiry probing his involvement in corruption when he was President from 2009 to 2018.

However, a week before former President Zuma’s imprisonment, a number of his supporters were seen picketing outside his Nkandla residence in an attempt to protect him and to threaten those who were planning to enforce the Court

order that he be jailed. This defiance is noteworthy when as a nation we take pride in the fact that we live in a democratic state where the law has to run its course and no individual is above the law.

On Wednesday 7 July 2021 just before midnight the former President handed himself over to the Estcourt Correctional Centre.

Immediately thereafter the riots broke out and for days we watched as parts of KwaZulu-Natal went up in flames and hundreds of citizens embarked on a looting spree and vandalised malls, factories and warehouses. We observed the South African Police Services being overwhelmed by the chaos and the violence spilling over to parts of Gauteng. President Cyril Ramaphosa addressed the nation a few days after the riots started, attributing aspects of the riots to ethnic mobilisation. However, the government’s stance changed to insurrection in the days following the President’s address. Again, we ask what then could be the real cause of the riots? Was it insurrection, ethnic mobilisation or other factors? There may very well be more that the government is unwilling to take into account.

Perhaps the unrest started off as a way for pro-Zuma supporters to demonstrate their loyalty, which then might have led to the comments relating to ethnic mobilisation. South Africa is a fairly young democracy and there are numerous issues that have been categorically ignored by the government since it came into power. However, some of these issues were put under a microscope during the unrest. We saw the riots developing into something else; we saw issues of criminality, racial tension and poverty coming to the fore.

The question then is – what has the government been doing to take care of the vulnerable for the past 27 years? What have they been doing to ensure that no 84-year-old would leave their comfortable home to loot a bag of maize-meal?

Moreover, the lack of unity and urgency in the ruling party became evident. After the riots there were rumours that the government was warned of the riots beforehand, but that they failed to act speedily and swiftly enough to avoid the eruption of chaos. We do not know what the true story is, but if they had noticed what was happening in Nkandla, days before Mr Zuma’s imprisonment, the impact of the riots could perhaps have been minimised.

What happened in those few days left us as citizens with a lot of questions: could this be the way civilians are saying “enough is enough” to the government?

Could the riots be the way citizens are forcing the government to listen, again? Could this be the future of South Africa or was it a once-off situation? As much as the government is saying that the riots were an orchestrated attempt to topple the government, these are the questions they should ask themselves, seeing how easy and willing the citizens were to go through with the plan.